2.6. Running an Unattended InstallationUnless you have only two or three servers, it's likely that you tire fairly quickly of being a high-paid installation babysitter, shoving disks and CD-ROMs in and out of machines while telling them all what country you live in. For all but the smallest of Windows shops, it is a good idea to use the Windows unattended installation featurethat is, installations run by files constructed by an administrator ahead of time that answer all of Setup's questions. This will save you time and make deploying and rolling out the operating system less tedious. You can automate Windows installations using one of three main methods. The first is through the use of unattended installation scripts, which are simple to configure and use but lack some flexibility in deploying to machines that are configured with different hardware. Scripts are best when you have a uniform hardware base. The second method is through the use of Remote Installation Services (RIS), a very useful feature that enables you to boot from the network and install Windows without any sort of distribution media. With this method, you have a lot of upfront configuration, but on the other hand, you can deploy to nearly any base of hardware, and you can customize certain aspects of the user experience during the installation, too. RIS is most appropriate when you have a diverse hardware base, plenty of network bandwidth, and computers that can boot from the network. The third and final method to use unattended installations is through the deployment of system images. It requires quite a bit of upfront installation, but it's a great timesaver when you need a computer reformatted and reinstalled in less than 30 minutes. Let's discuss each method. 2.6.1. Using ScriptsPerhaps the simplest method of automating a Windows Server 2003 deployment is to use scripts, or more specifically, unattended setup answer files. These files use a syntax not unlike that found in Windows 3.1 INI files, providing answers for questions such as computer name, your CD key, your name, where you live, and the like. Windows is instructed to read these files using an argument switch on its main setup program executable file, winnt32.exe. Table 2-5 lists all the switches this program will accept.

As we continue, you'll find that one of the simplest ways to control an unattended setup using a script is to call winnt32.exe from the command line using the following, assuming your script is in C:\Deploy:

Winnt32 /unattend:c:\deploy\winnt.sif

If you want to create a boot floppy for your unattended scripts so that you can simply truck it around to each workstation, just copy your script to the floppy and name it WINNT.SIF. Then, use the distribution CD-ROM to install Windows Server 2003 and boot directly from it, and Setup will automatically look for a file on a floppy in the A: drive named WINNT.SIF. If it finds one, Setup will read the instructions from it; if it doesn't, Setup will continue along a normal, user-interactive process. Regardless of how you instruct Setup to use an unattended script file, you must create one. The next section details this process. 2.6.1.1. Constructing unattended setup scriptsIt's easy to create the setup files used by an unattended setup in Windows Server 2003. Microsoft has included a utility called the Setup Manager, which is a graphical utility that asks you most of the questions Setup would ask during an installation, notes your answer, and constructs a WINNT.SIF answer file based on your inputs. Although the file that's created is very basic, it certainly works, and it's a great starting point for further customizations on your own. You'll see some of these options in action as we step through this process. To access the Setup Manager program, follow these steps:

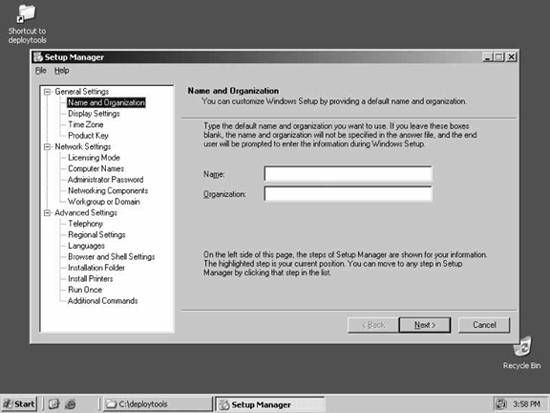

Once Setup Manager has started, you'll be prompted to either create a new answer file or edit an existing one. Choose to create a new one, and click Next. Now, you're presented with several options, depending on the particular application for which your new answer file will be used. You can create a basic unattended setup answer file, one that can automate the Mini-Setup program inside an installation that has been SYSPREPed, or a file that will control installations started with RIS. I cover the latter two options later in this section. For now, select to create a normal, basic, unattended setup answer file, and click Next. The next screen prompts you to choose the operating system for which you're creating an unattended install. You can create files for all editions of Windows XP and all editions of Windows Server 2003 except Datacenter, too, so the Setup Manager utility is more useful than it might otherwise appear. Choose to install Windows Server 2003 Standard Edition and click Next. At this point, you can now choose what level of "hands-off" you want to achieve: a completely hands-on installation with customized defaults read from the answer file, a fully hands-off installation that is started from the command line and not finished until Windows Server 2003 is completely installed, and most options in between. Choose Fully Automated to get the full breadth of options that Setup Manager can configure, and click Next. Here, Setup Manager offers to assist you in creating on your network a distribution share, or a file share that contains an entire copy of the Windows distribution files for the purposes of kicking off network-based automated installation sequences. For our purposes, click Set up from a CD because we just need to create an answer file, not generate an infrastructure for more complex rollouts. Click Next, accept the End-User License Agreement, and click Next once more. You have completed the wizard portion of the Setup Manager process, and the screen shown in Figure 2-7 is displayed. Figure 2-7. Setup Manager's detailed configuration screen

The remaining portion of Setup Manager involves customizing the many details of a Windows Server 2003 installation:

2.6.1.2. Privatizing the dynamic update processMicrosoft has begun releasing updated system and setup files that can be accessed by Setup for new installations. The net benefit of this initiative is the immediate updating of a newly deployed machine: many problems with the installation and upgrade process are eliminated with updated Setup executables. Although Microsoft allows these updates to be downloaded directly from their Windows Update service, you might want to run the dynamic update feature directly from your own network to control what updates are applied to which workstations or servers. To internalize this process, you must first download the dynamic update package, expand the files onto a network share, and then instruct the Setup program to use the localized version of the updated files and not those on the Windows Update web site. Here are the steps involved:

Once the download has completed, navigate through your filesystem to the place where you downloaded the update package. Double-click to open it. This will open a window that contains the package's contents, which should consist of a few cabinet (.CAB) files in a structure similar to that shown in Figure 2-8. Figure 2-8. Relative folder structure of a dynamic update package

To use the package, you must prepare the network share where the update package currently resides. Use the following command to complete this preparation, substituting the path to your network share for [path]:

Winnt32 /DUPrepare:[path]

Your share is now ready to use. For manual installations, you can use the /DUShare switch, specifying the path to the private dynamic update network share as an argument much like the /DUPrepare switch. But by default, in unattended installations dynamic update is disabled. You must include a line in the answer file to direct Setup to enable Dynamic Update and to specify a location where the updated packages can be found. Insert the following line into WINNT.SIF, in the [Unattended] section:

DUShare = "Path to privatized update package share"

2.6.1.3. Understanding and creating UDF filesYou might be wondering how to deploy several computers using one file when one crucial requirement remains unaddressed: how do you assign unique names to each installation? The answer lies in a single file: the uniqueness database file (UDF) , which provides a method for Setup to select values for variables that are unique to each individual system deployed. Some of the settings you can customize with UDFs include computer names, descriptions, and administrator passwords. The UDF files themselves are very simply constructed: like an old .INI file, they contain a list of identification values and pointers to full sections for each value later in the file. Here is a sample:

;SetupMgrTag

[UniqueIDs]

MERCURY=UserData

VENUS=UserData

EARTH=UserData

MARS=UserData

[MERCURY:UserData]

ComputerName=MERCURY

[VENUS:UserData]

ComputerName=VENUS

[EARTH:UserData]

ComputerName=EARTH

[MARS:UserData]

ComputerName=MARS

Note that under the UniqueIDs section, each value is identified along with the specific section in the standard unattended answer file to replace with the information in the UDF. Then, Setup reads the files, and in each individual computer's section it identifies the key to be replaced as defined in the file, and uses the replacement value given to actually make the change. How does it all come together in the end? Setup reads this file as instructed from the command line with an argument that tells it which value the current deployment is; that is, computer MERCURY, VENUS, EARTH, or MARS from my sample UDF. Once Setup reads in the value, it looks in the individual section and replaces the standard responses to the prompts given in the standard answer file with the specific ones listed in the UDF file. Issue the following command to kick off this process for computer EARTH, assuming this UDF file is called UNIQUE.UDF:

Winnt32 /unattend:c:\deploy\winnt.sif /udf:EARTH,unique.udf

2.6.2. Using RISIf you have a larger network in which you might receive 5 or 10 new machines a week to deploy initially, or in which you might need to completely reformat and reinstall some computers, you'll probably be longing for a more hands-off procedure than simple unattended scripts can give you. Microsoft, answering the call, has combined the convenience and features of unattended scripts with a tool that will allow your computers to boot from the network, select a preconfigured operating system image, and transfer that image to the hard drive of the target computer, all with just a few short answers at the beginning of the process. And it's not too good to be true, I promise. RIS makes it simple to install hundreds of machines by booting them off the network. It's remarkably flexible. You can perform three types of installations with RIS:

2.6.2.1. RIS limitationsRIS has a few key hardware limitations that you should be aware of. They are detailed as follows:

Some people have reported that it's not possible to install an RIS server on a machine that is functioning as a DHCP or DNS server. I'm happy to explain that that is false. In my test lab, I have two domain controllers, the first of which is also a DHCP server, a DNS server, and the RIS server for my network. I have no problems delivering any sort of image to any compatible client on the network. So, for the server consolidation advocates among you, I don't see any problems with using a server acting in multiple roles and as an RIS server as well. The software requirements for using RIS on your network are a little less stringent than the hardware RIS needs. You must have a DHCP server on your network, and you must be conducting RIS deployments in an Active Directory-based domain. RIS cannot handle static IPs, mainly because the PXE protocol has no such provision for them. RIS also uses DHCP as a mechanism to control the entry of unauthorized RISs to your network: before an RIS server can be used for deployments, it must be authorized within Active Directory. 2.6.2.2. Activating an RIS serverTo begin using RIS on your network, you must first authorize the RIS server as a DHCP server in your network. Then you install the RIS component onto your server, reboot, and add images. The process is outlined here:

Now it's time to actually install the RIS component on the server:

Finally, you must configure RIS and install an image to be used with RIS. In this example, we'll use a basic Windows XP Professional image that can be used to deploy on new computers later in the chapter. To get started, follow these steps:

The image copying procedure takes awhileon the order of 15 to 20 minutes per image, usually, depending on the speed of your server and CD-ROM. When you come back, though, the image will be installed into RIS and available for deployment. A reboot is not required.

2.6.2.3. Deploying an image to a clientOnce you've activated your RIS server and added images to deploy, you can then network-boot your client computers and transfer the images to them. The process to do so depends somewhat on the client computer. Some corporate-targeted PCs have options in the machine's BIOS to boot from the network, usually found in the area that determines the boot order of the storage devices. Other computers offer an option directly during the POST process to press F12 or some similar key to perform a network service boot. (The Compaq Armada E550 I'm using to write this now uses the latter method, whereas the Dell Precision Workstation that is my main desktop computer uses F10.) However, some older computersand yes, some newer computers as welldon't have the option to boot to the network in their BIOS or during POST. In this case, you'll need to use the RIS remote boot disk, mentioned earlier in this chapter as the saving grace for some machines. The Windows Server 2003 RIS disk supports 32 network adapters, all of which are PCI cards. If your Ethernet card is on that list, RIS will work even if the machine doesn't support PXE directly. To generate the network boot disk, navigate to the \RemoteInstall\Admin\i386 directory on your RIS server machine, and double-click RBFG.EXE. It will prompt you to insert a disk, which it will then format and reconstruct as the RIS remote boot disk. On to actually performing the deployment: insert the boot floppy or select the option to boot from the network, whichever applies in your case. If you use the boot floppy, you will see text similar to the following:

Microsoft Windows Remote Installation Boot Floppy

Copyright 2001 Lanworks Technologies Co., a subsidiary of 3Com Corporation

All rights reserved.

3Com 3C90XB / 3C90XC Etherlink PCI

Node: 00115A5E3E12

DHCP....

TFTP...........

Press F12 for network service boot

During that process, no matter which method you used to activate the network boot, the computer contacted a DHCP server and requested an address. That address was sent in a packet, containing a pointer to a server which has files needed to continue the RIS boot process. These files were transferred using the TFTP protocol, a cousin of the commonly used FTP protocol. Once the boot files were transferred, the program prompts you to confirm that you want to boot from the network. Press F12 to confirm this, and the blue background, text-based Client Installation Wizard appears. The first screen prompts you to enter your username, password, and account domain membership information. Then, you will be prompted whether to do an automatic or custom setup, or if you'd like to restart a previously failed setup attempt. Here is the difference between the two: automatic setups generate the computer name from a combination of your username and the computer's MAC address and set up an unattended installation with all the defaults. They also can retrieve existing data from Active Directory with regard to computer name and identification if you're redeploying a machine already configured in Active Directory. On the other hand, custom setups enable you to define a specific computer name for each RIS installation regardless of whether the machine is already set up in AD. Restarting a failed setup attempt is as functional as it is obvious; it begins either back at the text-based portion of Setup or at the graphical portion, depending on where in the process Setup stopped. If you get an error message stating that the operating system image you selected does not contain the necessary drivers for your network adapter and that Setup cannot continue, don't panic: refer to the OEM section a bit later in this chapter to take care of this problem.

2.6.2.4. Slipstreaming service packsBecause deployment and initial installation are now so convenient, you likely will find yourself longing for a streamlined post-Setup process. One of the most common tasks that must be performed before you can hand off a computer to an employee is installing the latest service pack and security updates. This is especially important in light of the latest wave of worm attacks, where newly installed machines can be infected with these worms before you even have a chance to install patches! All hope is not lost, however. Using a special command-line function of the service pack executable, you can instruct all versions of Windows 2000-, Windows XP-, and Windows Server 2003-based service packs to replace old files in a central distribution share with updated ones. This process, known as slipstreaming, works very well with RIS images because you already have the requisite distribution share. Let's walk through the process. You'll need the network/administrative (in other words, the full) version of the service pack for your respective platform, not the regular user version. To create the slipstreamed installation, follow these steps:

The files are then updated, and the process is complete. Slipstreaming is an easy way to make sure that new systems are updated before they're ever put into production. 2.6.2.5. Using the OEM option for further customizationSystem builders and solution integrators have a wonderful set of tools at their disposal to customize the first-use, or "out-of-box" experience. Manufacturers such as Dell and Gateway can use OEM installation options to install software, add support information, and generally make a plain-vanilla Windows installation their own. So, if they can do it, why can't you, the system administrator? After all, you're creating your own "brand" of computer, specifically for your company. Using the OEM folder, you can apply hotfixes during Setup so that your machines are as updated as possible, customize a browser, and add support information to the System applet in the Control Panel.

The Setup program is hard-coded to perform special actions when it finds certain files and folders within an $OEM$ folder in the installation directory or CD-ROM. To use this folder, create it at the same level as I386 in your RIS distribution share. (If you're using these instructions to create a special CD-ROM for computers that can't use RIS, create the $OEM$ folder inside I386. For some reason, the $OEM$ folder for RIS installations needs to be at the same level as the I386 folder.) Next, open your RIS script, RISTNDRD.SIF, which you can find at \\RISServerName\Reminst\Setup\English\Images\imagename\I386\templates, and find the [Unattended] section. There should be a line called OEMPreinstall with a value of No. Change this to Yes and save the file. This instructs Setup to look for the $OEM$ directory. First, let's add some updated drivers to our installation. Although Windows Server 2003 likely has reasonably up-to-date drivers for the most common hardware available, as time goes on new hardware obviously comes out for which Windows Server 2003 doesn't have native support. You can instruct Setup to look inside the $OEM$ directory for updated drivers and install them before the machine ever finishes the installation. The procedure we're about to go through works not only with Windows Server 2003, but also with any NT-based client operating system, including Windows 2000 and Windows XP. To make this work, follow these steps:

If you have multiple new drivers to install, separate each directory in the preceding command with a comma and a space. Make sure to enclose the paths in double quotation marks. Next, let's describe installing hotfixes using the $OEM$ options. When the OEMPreinstall option is set to Yes inside your unattended installation script, Setup looks for a file called CMDLINES.TXT inside the $OEM$ directory. If it finds one, it executes the commands listed in the file near the end of setup, before the first reboot. There are two catches to this: one, the programs that those commands listed in this file execute must reside in the $OEM$ directory, not in subdirectories above or below it; and two, the file CMDLINES.TXT itself must be inside the $OEM$ directory. Now, the hard part of this tip is actually finding the hotfixes and transporting them to the correct location for use within Setup. Microsoft recently reorganized the way hotfixes are obtained outside of the automated, user-blind Windows Update process. To obtain these "network administrator"-style patches, you must connect to the Windows Update service at http://windowsupdate.microsoft.com. Click Windows Update Catalog in the left bar. Then, follow these steps:

The really frustrating part about this process is that when you download these hotfixes, the Download Manager creates this supremely convoluted directory structure in which each particular hotfix resides in its own directory, with the executable file and an HTML document describing the fix. Because using CMDLINES.TXT requires that all the executable files to be run reside in the same directory, you have to manually extract the executables from this directory structure and copy them to the $OEM$ directory. Although it's not much of a problem with Windows Server 2003 hotfixes, if you happen to be deploying Windows XP without Service Pack 2 with this process, the 60-odd files you must drag and drop out of this structure will either drive you mad, put you into the advanced stages of carpal tunnel syndrome, or perhaps both. If any Microsoft people are reading this, give us the option to put all these executables into one directory!

The next frustrating part of this process is actually using the updates. Microsoft has said repeatedly that patch management would be quite a bit easier in the future, and the first step, it said, was to create patches with standard nomenclature and standard methods of execution and application. The news isnot surprisinglythat this utopia hasn't been reached yet. When you download hotfixes from Windows Update, some are named using one system, such as Q823980_WXP_SP3_ENU.exe, and others are named using some other system, such as WindowsXP_Q329834_ENU.EXE, and still others are named using what seems like no convention at all. Further, the switches that control the installation and execution of these hotfixes are not standard either. Some require /q and /z to install silently without reboots, while some require -q and -z, some need /noreboot, and others don't have switches at all. This is a sad state of affairs, and at this point, the only workaround is to manually test each patch on a system, note their behavior, and adjust the line in CMDLINES.TXT that calls that patch accordingly. You might think that with all these negatives, it's not worth the time it takes to create this $OEM$-based solution. But if you're installing machines using RIS and are not behind a firewall, the 45 minutes it takes to use Windows Update after the first reboot is more than enough time for a worm to infest your system before the applicable update is installed. These days, it's nearly a necessity to use this procedure. Hopefully, in the future there'll be a better way to perform these updates. But for now, once you've dragged the multiple hotfixes out of their individual directories, tested each one individually for its command-line behavior, and iced up your wrists, generate CMDLINES.TXT using the following formula:

[Commands]

"q823980_wxp_sp2_enu.exe -q -z"

"WindowsXP_Q329834_enu.exe -q -z"

Make sure the commands are fully surrounded in double quotes, and that the switches you use tell the hotfix to install silently and without a reboot. (If in doubt, run the executable with the /? argument: this will list the switches to which that program will respond.) 2.6.3. Deploying a System Image: RIPrep and SysprepIf RIS and unattended installations are great for deploying operating systems and hotfixes to a varied hardware base, RIPrep and Sysprep are wonderful helpers to deploy a complete "image" of a system, including the operating system, applications, customizations, settings, and restrictions, to a base of hardware that is identical in every respect. This is great for lab environments, and even better if your organization has a standard hardware base for all its new purchases within a year or two. The process is simple, too. You first create a prototype system, with the operating system, any applications, any environmental customizations, and anything else you want to pass on. Next, you run RIPrep, the Remote Installation Preparation Wizard, which gets rid of personal and security-related information and copies the image to the RIS server. You then deliver the image to the appropriate systems using the regular RIS network boot process. There is, however, a limitation to using RIPrepyou cannot image the following types of systems:

Let's pick up the step-by-step process after you've created your prototype system, the one you want to be duplicated. Install and configure a system exactly as you like. Then, follow these steps from your prototype workstation:

Reboot the prototype once RIPrep is finished. You'll note that it looks like Setup is being performed all over again; this is again because of RIPrep scrubbing the security identifier information from the prototype. Basically, it's all of the graphical setup, without the Plug-and-Play installation process. Just proceed through it, including reactivating the installation after Setup is finished, and you'll have the machine back for use. To deploy an image that was RIPrepped, simply go through the RIS boot process, and from the menus that allow you to select which image to deploy to the target computer, select the RIPrep image with the friendly description and help text that you specified in the previous procedure. The remainder of the process works exactly like a flat RIS installation. 2.6.3.1. Sysprep: the system preparation toolSometimes, though, using products such as Symantec Ghost and PowerQuest DriveImage is the quickest way to lay down an image onto multiple systems at once. The difference is that Ghost and DriveImage take what amount to photographs of the drive, copying whole partitions and physical disks without regard to individual files. RIPrep and RIS, on the other hand, look at individual files, which sometimes make it a little difficult to exactly replicate advanced prototype images. There's a catch, though: although products such as DriveImage and Ghost contain security identifier (SID) generators, which scrub out security identifier information in an image and replace it with a fresh, randomly generated SID, Microsoft doesn't support SIDs created with these generators. The company wants you to use Sysprep, which does just that in Microsoft's fashion, and in such a way that the company will support if you ever need technical assistance. Because the price is right (Sysprep is shipped free with Windows Server 2003), and it could save some headache in the future, it's a smart move to use it instead of the SID generators in third-party products.

Here's an overview of how Sysprep works:

To start Sysprepping a machine, follow these steps:

Sysprep will strip the SIDs off the system, scrub any personal identifying information from the image, and then shut down the machine. This is where you need to take over with your third-party tools to deploy these images. You also can run Setup Manager, as described earlier in this chapter, to create an unattended mini-Setup script that will make setup on newly deployed Sysprepped images a hands-off process. Setup Manager even includes an option whereby you are prompted to select the type of script to create to generate a Sysprep script. Set this, follow the screens using the guide presented earlier in this chapter, and copy the created filerenamed SYSPREP.INFto C:\SYSPREP on your image. |